Fact or Fiction??

Las Esperanzas, Coahuila is both fact and fiction. In Barefoot Dreams of Petra Luna, Las Esperanzas represents the many coal mining settlements in northern Mexico that were ravaged by the Mexican Revolution. In real life, Las Esperanzas was the birthplace of my grandmother. She always spoke fondly of it and with a name that translates to “the hopes”, I was convinced to make it Petra’s home.

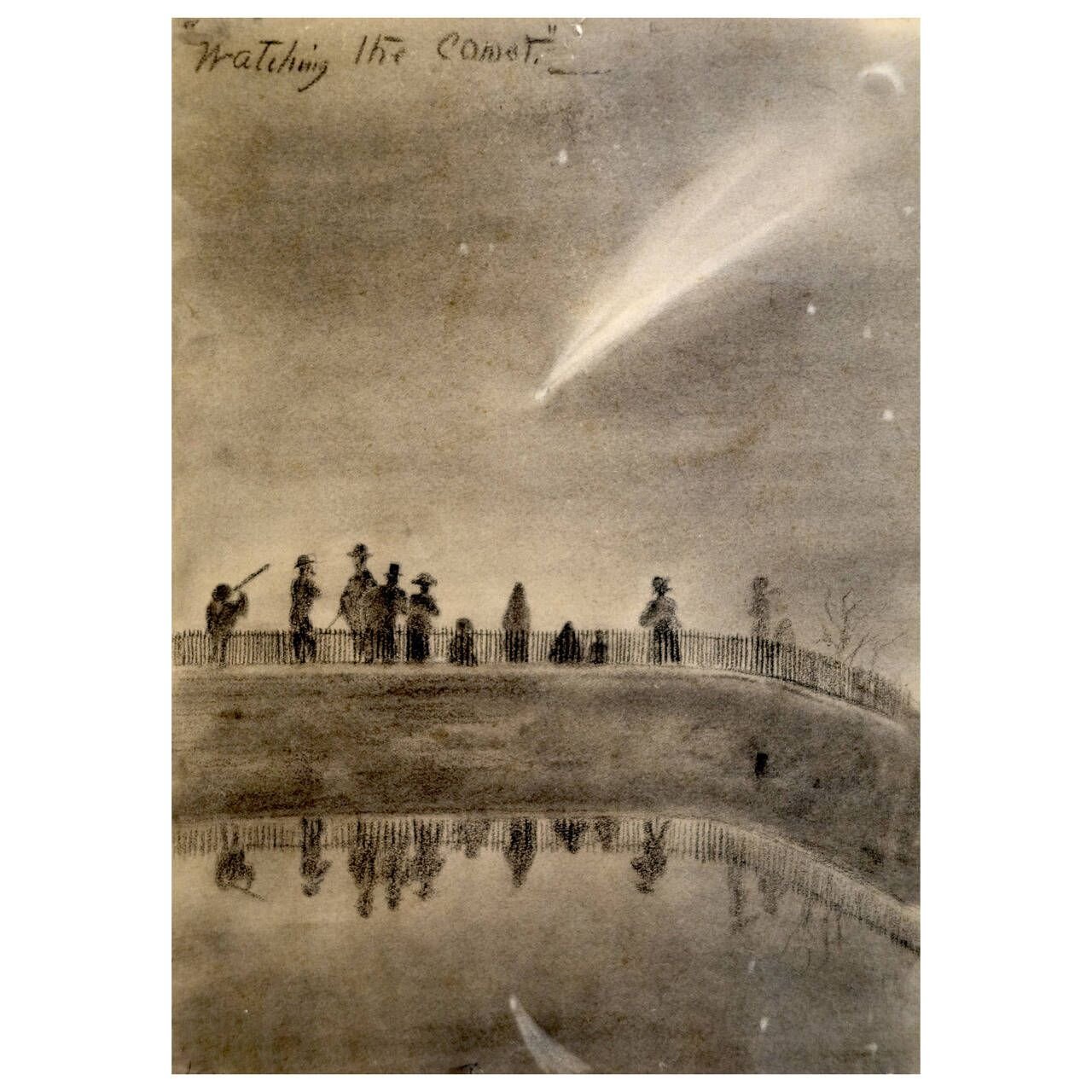

The “smoking star” that crossed the heavens in 1910 was a phenomenon my great-grandmother witnessed as a child. She told of how much it’d frightened people and swept them with pessimism. When I realized it was Halley’s Comet she’d seen, the same comet that had mesmerized me at age ten, I decided to start the story with its appearance.

Petra Luna’s character was inspired by both my grandmother and great-grandmother. The harsh poverty and prejudice they both faced were the same before, during, and even after the Mexican Revolution. Like Petra, my grandmother, Josefa Díaz, was a strong, bold girl who climbed trees and chopped wood to help feed her family. She too dreamed of one day learning to read and write, and once, her younger brother became so ill she had to beg for alms to help pay for his medicine, just like Petra does in the story. She found the experience so humiliating she swore that as long as she lived, her own children would never have to beg for alms. My great-grandmother, Juanita Martínez, inspired the novel at its core. Like Petra, she and her family escaped their burning village in 1913 during the Mexican Revolution. But unlike Petra, she was only nine years old when this happened, and it was she, her father, two siblings and two cousins who crossed the scorching desert by foot before reaching the border town of Piedras Negras, Coahuila.

The frantic crossing at the U.S.–Mexico bridge between Piedras Negras, Coahuila and Eagle Pass, Texas was a true event! As a child, this was one of my favorite stories because everyone told it with much enthusiasm. My mother’s eyes always brightened when she described the opening of the gate at the bridge. The day I found the newspaper article that depicted my great-grandmother’s story, I called my mother to let her know it was all true.

The big hole in the dirt floor of Petra Luna’s home was common during the Mexican Revolution. Some families hid men, boys, and even young women in them. My great-grandmother’s family had dug a hole to hide either her cousins or her father when the Federales came looking for men. This inspired the scene of Petra believing her cousin Pablo had hid inside the hole.

The story’s “coal” theme. Coal is mentioned several times in the book. Petra’s father is a coal miner, Adeline’s father is an engineer at a coal mine, the real border town of Piedras Negras, which means “Black Rocks”, is named after the region’s coal, and the amulet Petra squeezes throughout the story is a piece of coal. I spent my summers and almost every school break in the region of northern Mexico called “La Región Carbonífera” or “The Coal Region”. There’s a special culture, a pride per se, of the people who have lived there for generations. My grandfather, Santos Villanueva, was a coal miner in Nueva Rosita, the town where I was born. I vividly remember him boasting about living in a place rich with this black treasure. He’d pridefully point out the giant dark chimney that towered over the town and would happily talk about the mine’s history and contribution. Unfortunately, I also saw the terrible impact this type of work had on his health.

The foods are real. Pan pobre was a type of corn bread my grandmother ate on very special occasions as a child. Champurrado, a chocolate-based atole (a corn flour, hot beverage) was also a favorite. She grew up eating verdolagas (purslane weed) and quelites (pigweed amaranth), which was gathered in the wild and consumed raw, sautéed with eggs, or in soups and stews. Nopales or nopalitos are cactus pads that are stripped of their thorns, diced and eaten sautéed, with eggs or in soups or casseroles. Mesquite bean pods are sweet and can be chewed raw or the bean can be ground to make a type of flour.

The songs mentioned throughout the book are all real. The oldest one, “La Cucaracha”, is a folk song that can trace its roots back to Spain, but during the Mexican Revolution, the song’s verses evolved and new ones were added to describe the political climate of Mexico. “Adiós, Mamá Carlota” was composed in 1866 by Vicente Riva Palacio after the French Intervention in Mexico ended. The song “Las Coronelas”, a polka melody by Bonifacio Collazo Rodriguez, was composed after the Mexican Revolution but was inspired by the brave women who fought in it. The waltz “Alejandra”, which appears near the end of the novel, was composed by Enrique Mora Andrade who sold all the rights to the song for 25 pesos ($50 U.S. dollars) in 1907, which is the equivalent of $1,400 today. The waltz was composed as a request by Rafael Oropeza who was madly in love with a young maiden named Alejandra Ramírez Urrea. There are many other songs and corridos inspired by the Mexican Revolution, some which you may recognize: “Jesusita En Chihuahua”, “La Marcha de Zacatecas”, “Las Bicicletas”, “Las Tres Pelonas”, and the most famous, “La Adelita”.

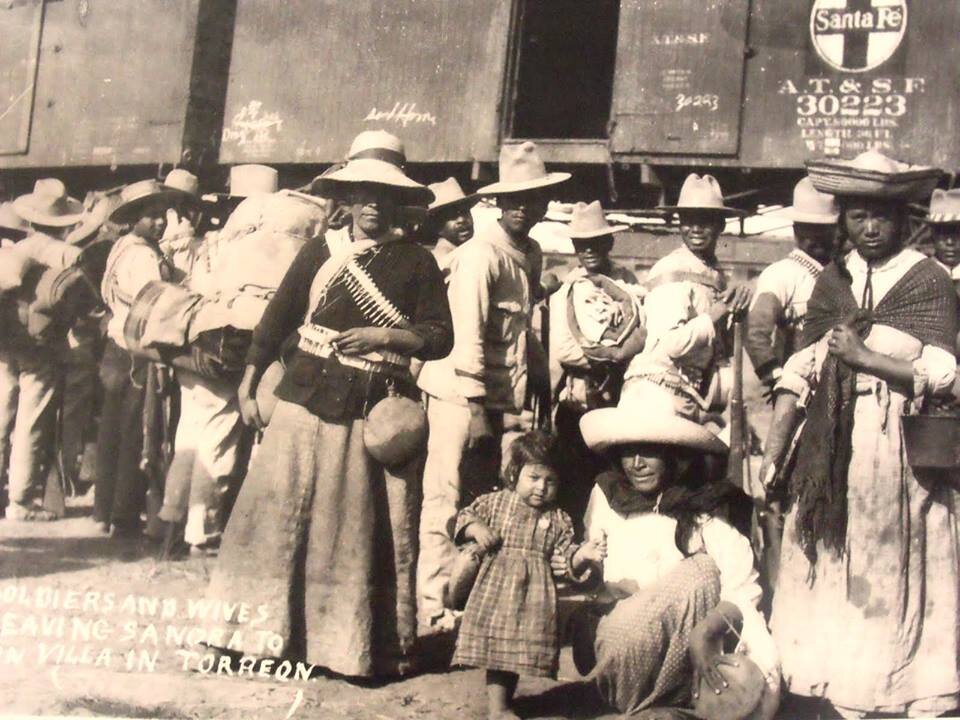

Soldaderas and Las Soldados were brave women who served on both the federal and rebel armies. Soldaderas, like the characters of Doña Amparo and Luz, were women who followed husbands, sons, brothers, and fathers into war, many of them towing along young children. They took charge of caring for their loved ones by scavenging for food, cooking, washing their clothes, treating wounds, sometimes engaging in combat, but always aiming to provide a sense of family and normalcy in the soldier’s life. Some soldaderas had no relatives fighting in the war but saw an opportunity to earn money by attending to soldier’s needs while at the same time not remaining vulnerable in a village empty of men.

Mujeres soldados, or soldadas, were women warriors like Marietta, who trained and fought along male counterparts. They rode horses, trained to use various weapons, carried out spy missions, and learned military tactics. Many of them had to initially disguise themselves as men by masculinizing their movements and voices. They wore men’s clothes and cut or pinned up their hair. Some women proved to be good, fearless fighters and, even after revealing themselves to be women, rose to the ranks of colonel and general and commanded brigades of men and women. Examples of real-life women soldiers are Margarita Neri, María Quinteras, Juana Ramona, Petra Herrera, and Valentina Ramírez.

Military trains played a major role in the Mexican Revolution. The train cars were loaded with food, supplies, equipment, horses, troops, and families. Once the cars were full, the rest of the soldiers, soldaderas and children, which could number in the hundreds, rode on the rooftops of trains and some under the boxcars on planks tied with knots. Many women and children fell to their deaths when a train turned a sharp curve or when it blew up or derailed.

Crossing a train bridge in the middle of a storm. The town in Mexico I visited often as a child, Sabinas, Coahuila, has a huge train bridge that crosses its wide river. There are many family stories my aunts shared with me of crossing that bridge at night or during storms because of wanting to visit friends that lived across the river. There were a few close calls, but lucky for them, nothing ever happened, nor did my grandmother ever find out!

Characters like Abuelita, Marietta, and Adeline are fictional but were inspired by stories of people I heard about from my mother and grandmother, from interviews and letters I came across in my research, and from personal observations, but there are four names mentioned in the book who are real people.

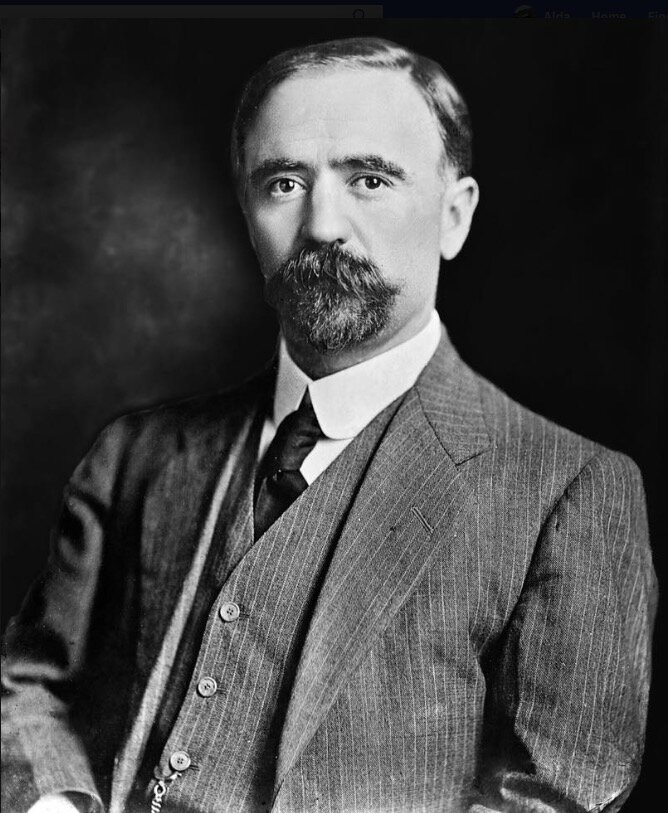

Francisco Madero: A rich hacendado from northern Mexico who sympathized with the poor

Porfirio Díaz: dictator of Mexico for over 30 years.

General Francisco “Pancho” Villa: an ally to Madero, led rebel forces in the north

General Victoriano Huerta: a general during Porfirio Diaz’s reign who later betrayed Madero